Аристотель «Поэтика»: Единство действия (1451a16)

8. Μῦθος δ᾽ ἐστὶν εἷς οὐχ ὥσπερ τινὲς οἴονται ἐὰν περὶ ἕνα ᾖ· πολλὰ γὰρ καὶ ἄπειρα τῷ ἑνὶ συμβαίνει, ἐξ ὧν ἐνίων οὐδέν ἐστιν ἕν· οὕτως δὲ καὶ πράξεις ἑνὸς πολλαί εἰσιν, ἐξ ὧν μία οὐδεμία γίνεται πρᾶξις. Διὸ πάντες ἐοίκασιν [20] ἁμαρτάνειν ὅσοι τῶν ποιητῶν Ἡρακληίδα Θησηίδα καὶ τὰ τοιαῦτα ποιήματα πεποιήκασιν· οἴονται γάρ, ἐπεὶ εἷς ἦν ὁ Ἡρακλῆς, ἕνα καὶ τὸν μῦθον εἶναι προσήκειν. Ὁ δ᾽ Ὅμηρος ὥσπερ καὶ τὰ ἄλλα διαφέρει καὶ τοῦτ᾽ ἔοικεν καλῶς ἰδεῖν, ἤτοι διὰ τέχνην ἢ διὰ φύσιν· Ὀδύσσειαν [25] γὰρ ποιῶν οὐκ ἐποίησεν ἅπαντα ὅσα αὐτῷ συνέβη, οἷον πληγῆναι μὲν ἐν τῷ Παρνασσῷ, μανῆναι δὲ προσποιήσασθαι ἐν τῷ ἀγερμῷ, ὧν οὐδὲν θατέρου γενομένου ἀναγκαῖον ἦν ἢ εἰκὸς θάτερον γενέσθαι, ἀλλὰ περὶ μίαν πρᾶξιν οἵαν λέγομεν τὴν Ὀδύσσειαν συνέστησεν, ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ τὴν [30] Ἰλιάδα. Χρὴ οὖν, καθάπερ καὶ ἐν ταῖς ἄλλαις μιμητικαῖς ἡ μία μίμησις ἑνός ἐστιν, οὕτω καὶ τὸν μῦθον, ἐπεὶ πράξεως μίμησίς ἐστι, μιᾶς τε εἶναι καὶ ταύτης ὅλης, καὶ τὰ μέρη συνεστάναι τῶν πραγμάτων οὕτως ὥστε μετατιθεμένου τινὸς μέρους ἢ ἀφαιρουμένου διαφέρεσθαι καὶ κινεῖσθαι τὸ ὅλον· ὃ γὰρ προσὸν [35] ἢ μὴ προσὸν μηδὲν ποιεῖ ἐπίδηλον, οὐδὲν μόριον τοῦ ὅλου ἐστίν.

Перевод М. Гаспарова

<Единство действия.>

[а16] Сказание бывает едино не тогда, как иные думают, когда оно сосредоточено вокруг одного <лица>, — потому что с одним <лицом> может происходить бесконечное множество событий, из которых иные никакого единства не имеют; точно так же и действия одного лица многочисленны и никак не складываются в единое действие. [а19] Поэтому думается, что заблуждаются все поэты, которые сочиняли «Гераклеиду», «Фесеиду» и тому подобные поэмы, — они думают, что раз Геракл был один, то и сказание <о нем> должно быть едино. [а22] А Гомер, как и в прочем <пред другими> отличается, так и тут, как видно, посмотрел на дело правильно, по дарованию ли своему или по искусству: сочиняя «Одиссею», он не взял всего, что с <героем> случилось, — и как он был ранен на Парнасе, и как он притворялся безумным во время сборов на войну — потому что во всем этом нет никакой необходимости или вероятности, чтобы за одним следовало другое; <нет>, он сложил «Одиссею», равно как и «Илиаду», вокруг одного действия в том смысле, как мы говорим. [а30] Следовательно, подобно тому, как в других подражательных искусствах единое подражание есть подражание одному предмету, так и сказание, будучи подражанием действию, должно быть <подражанием действию> единому и целому, и части событий должны быть так сложены, чтобы с перестановкой или изъятием одной из частей менялось бы и расстроивалось целое, — ибо то, присутствие или отсутствие чего незаметно, не есть часть целого.

Перевод В. Аппельрота

Фабула бывает едина не тогда, когда она вращается около одного [героя], как думают некоторые: в самом деле, с одним может случиться бесконечное множество событий, даже часть которых не представляет никакого единства. Точно так же и действия одного лица многочисленны, и из них никак не составляется одного действия. Поэтому, как кажется, заблуждаются все те поэты, которые написали «Гераклеиду», «Тесеиду» и тому подобные поэмы: они полагают, что так как Геракл был один, то одна должна быть и фабула. Гомер, как в прочемвыгодно отличается [от других поэтов], так и на этот вопрос, повидимому, взглянул правильно, благодаря ли искусству, или природному таланту: именно, творя «Одиссею», он не представил всего, что случилось с героем, например, как он был ранен на Парнасе, как притворился сумасшедшим во время сборов на войну, — ведь нет никакой необходимости <или> вероятия, чтобы при совершении одного из этих событий совершилось и другое; но он сложил свою «Одиссею», а равно и «Илиаду», вокруг одного действия, как мы его [только что] определили. Следовательно, подобно тому как и в прочих подражательных искусствах единое подражание есть подражание одному [предмету], так и фабула, служащая подражанием действию, должна быть изображением одного и притом цельного действия, и части событий должны быть так составлены, чтобы при перемене или отнятии какой-нибудь части изменялось и приходило в движение целое, ибо то, присутствие или отсутствие чего незаметно, не есть органическая часть целого.

Перевод Н. Новосадского

Фабула бывает единой не в том случае, когда она сосредоточивается около одного лица, как думают некоторые Ведь с одним лицом может происходить бесчисленное множество событий, из которых иные совершенно не представляют единства. Таким же образом может быть и много действий одного лица, из которых ни одно не является единым действием. Поэтому, кажется, ошибаются все те поэты, которые создали «Гераклеиду», «Тезеиду» и подобные им поэмы. Они думают, что так как Геракл был один, то отсюда следует, что и фабула о нем едина. А Гомер, который и в прочих отношениях отличается от других поэтов, и тут, как кажется, правильно посмотрел на дело [благодаря какой-нибудь теории, или своим природным дарованиям]. Создавая «Одиссею», он не изложил всего, что случилось с его героем, напр., как он был ранен на Парнасе, как притворился помешанным во время сборов в поход. Ведь ни одно из этих событий не возникало по необходимости или по вероятности из другого. Он сгруппировал все события «Одиссеи», так же как и «Илиады», вокруг одного действия в том смысле, как мы говорим. Поэтому, как и в других подражательных искусствах, единое подражание есть подражание одному предмету, так и фабула должна быть воспроизведением единого и притом цельного действия, ибо она есть подражание действию. А части событий должны быть соединены таким образом, чтобы при перестановке или пропуске какой-нибудь части изменялось и потрясалось целое. Ведь то, что своим присутствием или отсутствием ничего не объясняет, не составляет никакой части целого.

Translated by W.H. Fyfe

A plot does not have unity, as some people think, simply because it deals with a single hero. Many and indeed innumerable things happen to an individual, some of which do not go to make up any unity, and similarly an individual is concerned in many actions which do not combine into a single piece of action. [20] It seems therefore that all those poets are wrong who have written a HeracIeid or Theseid or other such poems. They think that because Heracles was a single individual the plot must for that reason have unity. But Homer, supreme also in all other respects, was apparently well aware of this truth either by instinct or from knowledge of his art. For in writing an Odyssey he did not put in all that ever happened to Odysseus, his being wounded on Parnassus, for instance, or his feigned madness when the host was gathered(these being events neither of which necessarily or probably led to the other), but he constructed his Odyssey round a single action in our sense of the phrase. And the Iliad the same. As then in the other arts of representation a single representation means a representation of a single object, so too the plot being a representation of a piece of action must represent a single piece of action and the whole of it; and the component incidents must be so arranged that if one of them be transposed or removed, the unity of the whole is dislocated and destroyed. For if the presence or absence of a thing makes no visible difference, then it is not an integral part of the whole.

What we have said already makes it further clear that a poet’s object is not to tell what actually happened but what could and would happen either probably or inevitably. The difference between a historian and a poet is not that one writes in prose and the other in verse — [1451b][1] indeed the writings of Herodotus could be put into verse and yet would still be a kind of history, whether written in metre or not. The real difference is this, that one tells what happened and the other what might happen. For this reason poetry is something more scientific and serious than history, because poetry tends to give general truths while history gives particular facts.

By a «general truth» I mean the sort of thing that a certain type of man will do or say either probably or necessarily. That is what poetry aims at in giving names to the characters.1 A «particular fact» is what Alcibiades did or what was done to him. In the case of comedy this has now become obvious, for comedians construct their plots out of probable incidents and then put in any names that occur to them. They do not, like the iambic satirists, write about individuals. In tragedy, on the other hand, they keep to real names. The reason is that what is possible carries conviction. If a thing has not happened, we do not yet believe in its possibility, but what has happened is obviously possible. Had it been impossible, it would not have happened. [20] It is true that in some tragedies one or two of the names are familiar and the rest invented; indeed in some they are all invented, as for instance in Agathon’s Antheus, where both the incidents and the names are invented and yet it is none the less a favourite. One need not therefore endeavor invariably to keep to the traditional stories with which our tragedies deal. Indeed it would be absurd to do that, seeing that the familiar themes are familiar only to a few and yet please all.

Translated by S.H. Butcher

Unity of plot does not, as some persons think, consist in the unity of the hero. For infinitely various are the incidents in one man’s life which cannot be reduced to unity; and so, too, there are many actions of one man out of which we cannot make one action. Hence the error, as it appears, of all poets who have composed a Heracleid, a Theseid, or other poems of the kind. They imagine that as Heracles was one man, the story of Heracles must also be a unity. But Homer, as in all else he is of surpassing merit, here too — whether from art or natural genius — seems to have happily discerned the truth. In composing the Odyssey he did not include all the adventures of Odysseus-such as his wound on Parnassus, or his feigned madness at the mustering of the host — incidents between which there was no necessary or probable connection: but he made the Odyssey, and likewise the Iliad, to center round an action that in our sense of the word is one. As therefore, in the other imitative arts, the imitation is one when the object imitated is one, so the plot, being an imitation of an action, must imitate one action and that a whole, the structural union of the parts being such that, if any one of them is displaced or removed, the whole will be disjointed and disturbed. For a thing whose presence or absence makes no visible difference, is not an organic part of the whole.

Translated by I. Bywater

The Unity of a Plot does not consist, as some suppose, in its having one man as its subject. An infinity of things befall that one man, some of which it is impossible to reduce to unity; and in like manner there are many actions of one man which cannot be made to form one action. One sees, therefore, the mistake of all the poets who have written a Heracleid, a Theseid, or similar poems; they suppose that, because Heracles was one man, the story also of Heracles must be one story. Homer, however, evidently understood this point quite well, whether by art or instinct, just in the same way as he excels the rest i.e.ery other respect. In writing an Odyssey, he did not make the poem cover all that ever befell his hero — it befell him, for instance, to get wounded on Parnassus and also to feign madness at the time of the call to arms, but the two incidents had no probable or necessary connexion with one another — instead of doing that, he took an action with a Unity of the kind we are describing as the subject of the Odyssey, as also of the Iliad. The truth is that, just as in the other imitative arts one imitation is always of one thing, so in poetry the story, as an imitation of action, must represent one action, a complete whole, with its several incidents so closely connected that the transposal or withdrawal of any one of them will disjoin and dislocate the whole. For that which makes no perceptible difference by its presence or absence is no real part of the whole.

Traduction Ch. Emile Ruelle

I. Ce qui fait que la fable est une, ce n’est pas, comme le croient

quelques-uns, qu’elle se rapporte à un seul personnage, car il peut arriver à un seul une infinité d’aventures dont l’ensemble, dans quelques parties, ne constituerait nullement l’unité; de même, les actions d’un seul peuvent être en grand nombre sans qu’il en résulte aucunement unité d’action.

II. Aussi paraissent-ils avoir fait fausse route tous Jes poètes qui ont composé l’Héracléide, la Théséide et autres poèmes analogues; car ils croient qu’Hercule, par exemple, étant le seul héros, la fable doit être une .

III. Homère, entre autres traits qui le distinguent des autres poètes, a celui-ci, qu’il a bien compris cela, soit par sa connaissance de l’art, soit par un génie naturel. En composant l’Odyssée, il n’a pas mis dans son poème tous les événements arrivés à Ulysse, tels, par exemple, que les blessures reçues par lui sur le Parnasse, ou sa simulation de la folie au moment de la réunion de l’armée. De ces deux faits, l’accomplissement de l’un n’était pas une conséquence nécessaire, ou même probable de l’autre; mais il constitua l’Odyssée en vue de ce que nous appelons l’« unité d’action ». Il fit de même pour l’Iliade.

IV. Il faut donc que, de même que dans les autres arts imitatifs, l’imitation d’un seul objet est une, de la même manière la fable, puisqu’elle est l’imitation d’une action, soit celle d’une action une et entière, et que l’on constitue les parties des faits de telle sorte que le déplacement de quelque partie, ou sa suppression, entraîne une modification et un changement dans l’ensemble; car ce qu’on ajoute ou ce qu’on retranche, sans laisser une trace sensible, n’est pas une partie (intégrante) de cet ensemble.

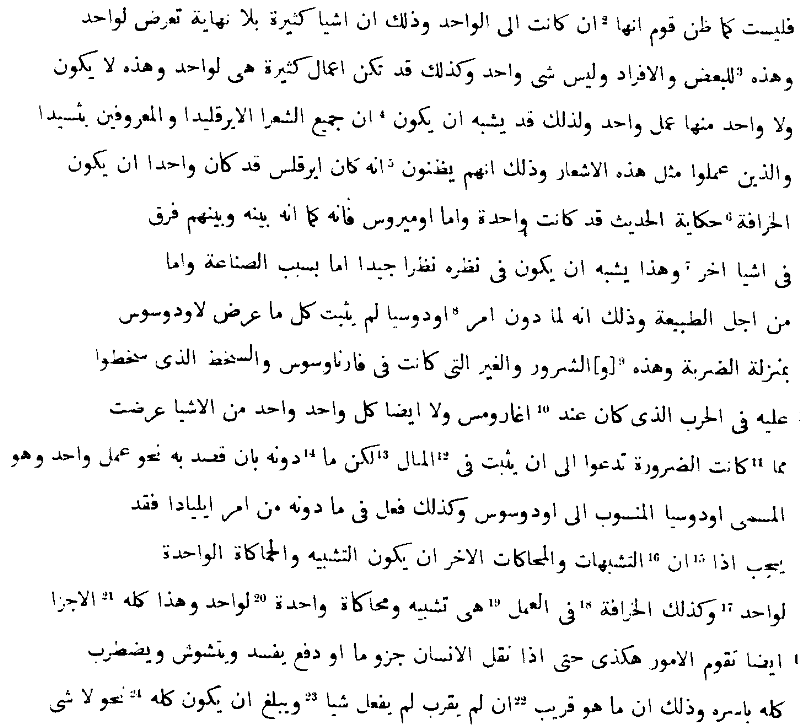

Перевод Абу-Бисра, не позднее 940 г.